Playing on the Court of Life

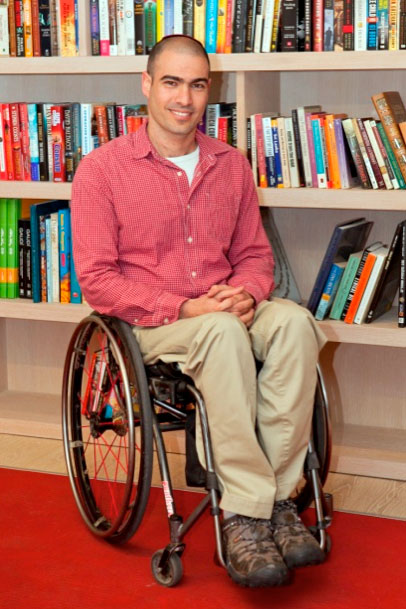

His injury turned him from an officer in an elite unit into a disabled guy. Competitive basketball changed his world and proved to him that even in a wheelchair you can remain a warrior, and win, too.

Once every few weeks, a group of IDF officers comes to visit Beit Halochem (a rehabilitation, sports and recreation center for disabled veterans) in Jerusalem – regiment commanders, base commanders, squadron commanders, etc. – for a day of introduction. During the course of the visit, the guests take off their military uniforms, put on sports clothes, sit in wheelchairs in the gym and, for the first time in their lives, begin practicing basketball from wheelchair height, usually against a team of disabled players.

“Here, I invite the commanders to move from their comfort zone of authority to a zone of disability,” explains Roei Ben Tolila, a player on the Israeli national wheelchair basketball team for the last 11 years, and the project’s creator. “Every such simulation, which takes about an hour and a half, completely changes their conception of disabled people and the difficulties and constraints that we have to contend with. I think that today there isn’t a single IDF regiment commander who hasn’t sat, even for just one hour, in a wheelchair. Today it’s a mandatory step for all officers. The very fact that these officers see the world for the first time from our height, will in my opinion turn them into better commanders in the future.”

Why?

“Because in order to win at sports, just like winning in battle or in business, you must have teamwork, to know how to cooperate with the other players on the team – to defend your basket together, to pass the ball on the offense. Alone you’ll never succeed. Wheelchair basketball is a game where if you try to be the star and dribble alone time after time, you’ll lose.”

Team spirit at Beit Halochem

Meaning?

“You need the ball to pass from player to player, with all of the players on the team playing the same melody in harmony.

That’s the key to success. You ask what turns a regular team into a winning team, and you get the answer in wheelchair basketball. Precisely because the player in a wheelchair is limited, he needs to constantly raise his head and look around for resources, in this case other players on his team, who can help him and move him forward, just like in life. This great understanding is also the metaphoric axis in the workshops I conduct as part of the business I established called Roim, to develop leadership for commanders and managers. The understanding is that the winners are the ones who work together.”

This understanding is correct for sports, for the army, and also for many other areas of life.

“True. Groups come from overseas to visit us here, specifically to experience this thing called wheelchair basketball. I often ask these visitors what led them to visit Beit Halochem, and their answers move me. They say, ‘We’ve already been to Israel and visited Massada and the Western Wall, and every place we went, there was a guide who told us the story of that place. But here, at Beit Halochem, you don’t need to tell us the story because you are the story. Each and every one of you is the story of the State of Israel.’”

Coping with disability

Ben Tolila was born 36 years ago on Kvutsat Yavne, a religious kibbutz, the fourth of five siblings. In 2000, he enlisted in the Maglan special forces unit, and underwent a grueling combat training course lasting twenty months. Even at that point he was identified by the unit’s commanders as having great promise, and after completing the course he was sent to an officers’ course. Afterwards, he returned to his unit, at first as a team commander and later as a deputy company commander.

“We’re the generation of Second Intifada soldiers,” Ben Tolila recalls the stormiest period of his life. “Our goal was to catch the terrorists in their homes, long before they came to carry out attacks on our streets. Most of our operations then were arrests. Almost every night we would go out quietly, in the dark, sometimes on foot and sometimes in vehicles, and do the job.”

Ben Tolila was injured in an operation he led in 2004, in the refugee camp on the outskirts of Jenin, when he was already a career officer. The force had surrounded the home of the target, when a soldier in a parallel force opened fire and hit Ben Tolila accidentally. The bullet entered his body through the right arm, hit his spine and caused paralysis. Ben Tolila was evacuated by helicopter in serious condition to the Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, where he underwent surgery and was hospitalized in the intensive care unit, sedated and on a respirator. When he recovered, he was sent to Tel Hashomer for rehabilitation, for six months. During that entire period, Maya was at his side – his then girlfriend, who later became his wife and his partner in life.

“Maya went through all that with me and she is a very significant part of my rehabilitation,” Ben Tolila explains. “I want to emphasize the fact that the concept of rehabilitation refers not only to the physical aspect, but also to your relationships with many people who knew you before the injury as a heroic commander who knows how to solve problems, and suddenly have to deal with a guy who is disabled and limited.”

And Maya accepted you just as you are?

“At the beginning, I suggested that she leave me. I told her, ‘You decided to date an officer in an elite unit, not a disabled guy in a wheelchair.’ But she insisted on staying. Happily for me, I was lucky enough to find a woman who even back then saw my true qualities, far beyond what I saw, and chose to live her life and raise a family with me.”

Entrepreneurship, studies and business

Entrepreneurship, studies and business

Five years ago, Roei and Maya finished building their home in Ma’ale Beitar in the Jerusalem hills, where they are raising their four children. The Ministry of Defense assisted in financing the land purchase and construction work. “When we were just starting out, there were those who warned us against the whole turmoil, but in the end we enjoyed all of the stages, from the planning to the actual construction. It’s exciting to build a house from the foundations.”

In the 13 years that have passed since his injury, Ben Tolila has completed a bachelor’s degree in social work at Bar Ilan University, and a master’s degree in organizational consulting at the College of Management in Rishon LeZion. In between degrees, he also established his personal business, Roim, through which he facilitates workshop groups in leadership, including business leadership, with a program he developed himself.

At the same time, Ben Tolila has been serving for the past few years as the professional director of Amutat Maglan’s mentoring program, which helps alumni of the elite unit to realize their personal dreams. Each year, they connect 12 unit alumni studying for an undergraduate degree to 12 successful leaders in various fields – business leaders, company directors, hospital unit directors, etc. The mentor-leaders guide the former soldiers throughout the period, and help them to develop any wish or idea they have in mind.

“The subject of entrepreneurship is very popular for Maglan alumni,” Ben Tolila reveals. “There is a unique atmosphere in the unit of creativity, competitiveness, aspiration and ambitiousness.”

And how is this manifested in practice?

“The basis of our approach is that if you have an idea, it would be a shame to ignore it. So why not? For one person it could be an innovative product that he wants to develop, and another could have a vision of being CEO of his own company. In each group, there are 12 alumni who have 12 meetings each with the 12 mentors who guide them. We recently completed the third successful program, and the fourth will soon begin.”

Basketball changed his world

Just a few days after our meeting at the beginning of summer, Ben Tolila set out with the Israeli national wheelchair basketball team to the European championship tournament on the Spanish island Tenerife. During this championship, as in the prior one two years ago, the Israeli team reached a respectable eighth place, again establishing its status among the best European teams. For Ben Tolila, one of the team’s guards, the encounter with this demanding sport in his early 20s was a significant turning point in his struggle with the concept of disability.

“At the start of my rehabilitation period I was very sad,” he remembers. “Being an officer in Maglan is a powerful emotional experience. You feel that you are invincible, that you are above life itself, and then you get this slap in the face. I met with a lot of psychologists and social workers after my injury, but they didn’t know how to help me. Until one day I chanced upon the basketball court at the Tel Aviv Beit Halochem, and what I saw there changed my entire world.”

What did you see there?

“Disabled people like me, even amputees, who go to the basketball court after work, change out of their button-down shirts into sports clothes. Magic. I understood then, for that first time, that you can do both. Some of the players weren’t even disabled, but they came to play because their father is disabled and they wanted to play with him. For me, a former soldier in an elite unit, it was the closest thing to the camaraderie of a team of soldiers, but playing on the court of life.”

Did comparisons to Maglan also come up on the court?

“In the special forces unit Maglan, we talk in the language of winning – how to win together. That’s the driving force. When I started playing basketball, I realized that you can speak the same language even when you’re sitting in a wheelchair. Look, psychologists recommend that disabled IDF veterans join support groups, but it’s not so simple. For tough soldiers, it’s hard to talk about their pain and expose their difficulties,” he explains. “At basketball I met the most effective support group I could hope for. Here, you don’t need to talk about where you were injured and what your problems are, but just to deal with how we can win together. Without words.”

In 2009, after playing for a few years on the team at the Tel Aviv Beit Halochem, Ben Tolila embarked on another exciting adventure – establishing a competitive wheelchair basketball team at the Jerusalem Beit Halochem, which he calls his second home. Along with his good friend David Deri, a disabled veteran from Jerusalem, the two began to recruit players for the new team.

“The Tel Aviv team members are very important to me, but I felt that the people in Jerusalem deserved a team of their own,” says Ben Tolila. “It’s hard to travel three or four times a week from the Jerusalem hills to the Tel Aviv Beit Halochem, and the family pays the price. Today, I live a 20-minute drive from the Jerusalem Beit Halochem, and I am involved in every little thing connected to the team. It was clear to us that this was something beyond just basketball, a kind of community, from the very beginning.”

Do you like to play basketball?

“After being injured, you discover that the range of sports available to you as a disabled person has decreased significantly, and basketball seemed like the option that most suited me. It’s a gift for me. I never would have gotten to play in five European championships in an Israeli national team uniform if I had not been injured,” he says. “We are about to go to a two-week tournament in Tenerife and I am just as excited as the first time.”

Why?

“Because at these championships you take your body – or what’s left of it – to the limit of its ability. In order to be part of a winning team, a lot of things need to come together, in particular team and interpersonal harmony. At the previous championship, we were defeated in one of the evening games against the strong team from Holland. At ten o’clock the very next morning we had to gather

ourselves and find the strength to go out on the court and play our most important game, against the Swedish team, Ben Tolila notes. “In the end, we beat the Swedish team by two points and felt like we were on a rollercoaster. It was an amazing experience.”

A supportive Jerusalem crowd

An amazing and unusual experience awaits the visiting teams that come to play against the wheelchair basketball team at the Jerusalem Beit Halochem, both at its home court and at the big and important games that are held sometimes on the court of a huge arena. The team encounters the noisy and supportive Jerusalem crowd, in extreme contrast to the quiet and polite audience of most of the other teams in the premier league.

“The first game to which we invited an audience was a very strange experience for us,” Ben Tolila recalls. “We came with the energy of an American ice hockey team, and we met a Philharmonic audience. We were in shock. At the end of the game, I went up to one of my fan friends who is known to be a noisy guy. I asked him, ‘What’s this silence?’ and he said, ‘Listen, I don’t feel comfortable being against them. They’re also disabled. How can I boo a disabled player standing on the penalty line before his throws?”

Good question. How did you answer him?

“I told him that they are players and people just like me and him, who are very happy that for the first time in their lives someone is booing them. I really believe that when someone boos you, it defines you and increases your desire to prove that you are good at what you do. When you don’t annoy anyone, you don’t exist. I explained to him that booing the opposing team is what every audience of every quality sport in the whole world does, and it’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Ben Tolila continued. “After that, we took on another project – before every home game, we host a team to play us on wheelchairs – youth, soldiers, students, new immigrants, and others. We saw that after they also sat on wheelchairs and played the game from our point of view, something changed in them in terms of their attitude to the game as fans. In that respect, when they come today to cheer us on during a game, they don’t see disabled people, they just see people – and that’s a huge change in perception.”

The players on the other teams don’t suffer from it?

“Players from all of the league teams love to play at the Jerusalem volcano, because there is no such atmosphere at any other court in the league. How many times in their lives do they have the opportunity to play against so many spectators who know the game and are so involved in it? Today, our whole team is made up of players from Jerusalem and the surrounding area. We don’t bring players from outside. We may have gone down a little in quality,” he comments, “but that’s not so bad. We know that we’re building something for the long-term, and that’s what drives us, both in losses and in wins. When we started with this idea, 30 people came to watch the finals. Today, at least 150 fans come to each regular game, usually more. The finals, which took place this year at the Malha arena, had an audience of 3,000. Amazing.”

And who won?

“Last year we played in the finals in Tel Aviv against the Tel Aviv Beit Halochem. We won, but I didn’t feel a real victory. This year we also played in the finals at the Malha Arena against the Tel Aviv Beit Halochem. This time we lost,” Ben relates, “but I left with a feeling of victory that I’d never felt before. It redefined my entire concept of winning.”

Comments are closed.