On February 25, 1996, Dana Pinhasov’s world changed forever. It was a Sunday morning when the then 21-year-old began to make her way back to base after the weekend. She was a medic with the border police – born and raised in Jerusalem – and each morning her mother would drive her from their loving family home in Katamon to the Central Bus Station.

Dana caught the number 18 bus at 6:15 am. When she began her journey, she sat behind the driver. Then, close to Jaffa Gate, the bus stopped, and a suicide bomber boarded. He detonated his bomb on Jaffa Road, just before arrival at the Central Bus Station.

“The place I was sitting was horrible, because it was exactly above the gas tank,” Dana recalls. So, as the bus erupted into a fireball, Dana was the first to feel the impact. She hit her head on the glass window, losing consciousness as her lower body was engulfed in flames.

“I was there for about 20 minutes before they started taking out the dead bodies and realized that I was somehow alive,” says Dana, who was considered one of the “lucky” ones.

News footage of the incident is shockingly grim: the mangled skeleton of the charred bus is all that remains, as lifeless bodies lie strewn across the road up to 100 meters away, stretchers rush by in a blur, bundled into the backs of ambulances by soldiers and paramedics, while Orthodox workers meticulously search for and gather scattered body parts for burial, amidst a sea of metal shards and carnage.

The terrorist had worn a 10-kilogram bomb packed with nails, ball bearings and bullets in the attack which tragically killed 26 (17 civilians and nine soldiers), and injured 49 others.

Dana was rushed to Hadassah hospital at Ein Kerem. For the first four hours, she was known only as “unidentified victim number one”. Once she was finally identified, Dana’s parents were called and told to say their goodbyes. Her burns were very severe as was the internal damage sustained to her lungs.

Dana’s father told news reporters shortly after arriving at the hospital, “I said to myself, I am going to collect my daughter’s corpse.”

But her parents and three brothers had faith, and kept a constant bedside vigil while she remained unconscious and connected to a respirator. “It’s a matter of time. With God’s help she’ll make it. She’s strong enough to make it,” Dana’s father told media at the time.

Ten days later, Dana awoke, “but with no recollection of how I got there”, she shares. … They told me what happened, and I was like, okay … that kind of thing happens to other people… But that moment of consciousness marked the beginning of “three long, excruciating months of pain”.

“I had 17 surgeries, skin transplants and skin grafts,” she reveals. “I screamed. In order to prevent infections with burns, they have to cover you all the time, so that means bandage replacement two or three times a day.”

And then came time for her first bath. Dana asked for her father – “the only person I knew who would be able to cope with what I was going through, so I said, I want him next to me.”

It was also the first time that Dana saw her legs since the bombing. The nurses put her in the tub, and with her father holding her hand, they started peeling back the rounds of bandage.

Dana kept her focus on her father and through a torrent of tears they tried to convince and reassure each other that it “wasn’t so bad”.

“My legs looked like a quilt. Small squares of different colors attached by a staple gun to one another. I don’t think there is anything that could have prepared me for that.”

There was also the emotional damage that Dana had to endure. “I was in pain and thought I didn’t deserve this. I am 21. Why? Why did I get this?” She tried to push away her boyfriend, but he wouldn’t leave. “I didn’t want anyone to stay because he is sorry for me. So, I was even more mean … And he still didn’t go!

Dana asked him why he remained by her bedside. His response was simple: “You are still the same person I fell in love with and I’m not going anywhere.” Dana’s boyfriend never left. Two years after her injuries, they married.

And despite her scars, she proudly wears shorts in summer. “But I think at that point in time, I saw my life end,” she tells. “I used to love wearing shorts and mini-skirts and going to the pool, and oh my God, what will happen to me now I’m scarred. Everyone will look at me, everyone will stare at me.”

After three months of treatment at Hadassah Ein Kerem, Dana moved on to rehabilitation.

“It took me a couple of weeks there to realize that my body may have been completely dysfunctional, but my brain was completely okay….” Dana already had her sights set on returning to work. “They thought I was crazy – but I did it,” she affirms.

This was when Beit Halochem in Jerusalem entered her life. Dana underwent physiotherapy and hydrotherapy at the Jerusalem center, “and I got to spend time with people who were worse than what I was. They were amputated, they were in a wheelchair, and they actually showed me that there is a light at the end of the tunnel”.

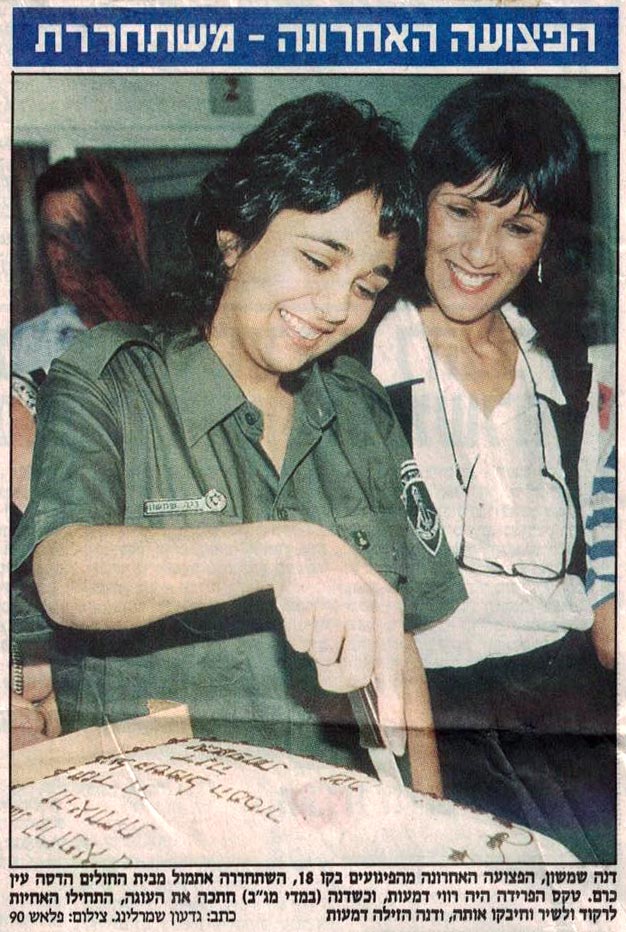

Dana returned to work with the border police. “They thought I was crazy – but I did it.”

“You can play sport, practice art, and you can have a family. You can have a normal life and it’s not the end of the road for people like me.” Dana took it day by day. She had to learn how to walk again, first with a walker, then a cane – “but I didn’t want to use all those things. I wanted to walk normally. I didn’t want anyone else to see that I had any kind of difficulties”. And soon she did.

“I think that only my parents’ strength walked me through those painful moments and made me realize that I’m much more than my injury. And today, I know that I am much more than

that. But it took a long process to understand and to accept who I am.”

Dana soon returned to the border police for the first half of each day, before her afternoon treatment at Beit Halochem. In time, she became a mother to four children. But the combination of her injuries, motherhood and working for the border police were eventually too much, and by the age of 27, Dana was forced to retire. “I still wanted to be influential in the world – and it didn’t have to be a day job.”

She started volunteering, first in children’s shelters, then retirement homes, and then it occurred to her to give back to the place that gave her so much.

Dana began volunteering at Beit Halochem “to show younger veterans that there is a light at the end of the tunnel” – but she still had more to contribute.

She was elected the first woman to sit on the national board of directors of Beit Halochem Israel and oversaw the building of the fourth Beit Halochem center facility, based in Beer Sheva, and the beginning of a fifth campus at Ashdod.

“Each year, I have two birthdays, November 7, the day I was born, and February 25, the day I was reborn,” shares Dana.

For the past few years, she has penned a letter to herself on the anniversary, to understand “how that single event has affected the person I am today”. In last year’s letter, Dana mused on all that she went through at the time of the bombing.

“I could, back then, 22 years ago, have given up. I was disabled, a scarred woman, and terrified of the new situation. But something within me simply went on without going over the obstacles.”

She writes of how she eventually learned to “embrace herself with love” in order to flourish, and with acceptance of her new reality was able to reinvent herself to create a full life.

“I knew that if I pause for a moment to feel sorry for myself, or to cry for my fate, life will go on without me. Today, I understand that this is one of the gifts that I received when I chose to continue living – that inner understanding that we must continue forward even if bumps on the road slow us down.”

By Rebecca Davis

Comments are closed.