The Ultimate Warrior

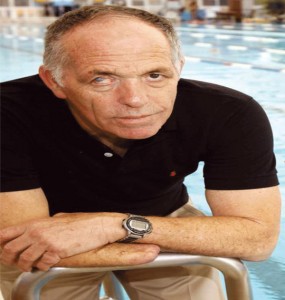

By Avi Zur, July 2013 | Photographs by Ariel Bsor

I must confess that for 12 years I have been trying to get Col. (res.) Ilan Egozi to grant me an interview for “Halochem” magazine for twelve years he has politely declined: “Forget about it”, he says, “I don’t have an interesting story. You should interview the young disabled veterans. They are much more appealing”.

On the occasion of the Independence Day edition I tried again. Perhaps it is his retirement from the position of Executive Director of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Fund, or just his age, 69, which softened him a little, but this time, after the Chairman of the ZDVO put pressure on him, he finally agreed.

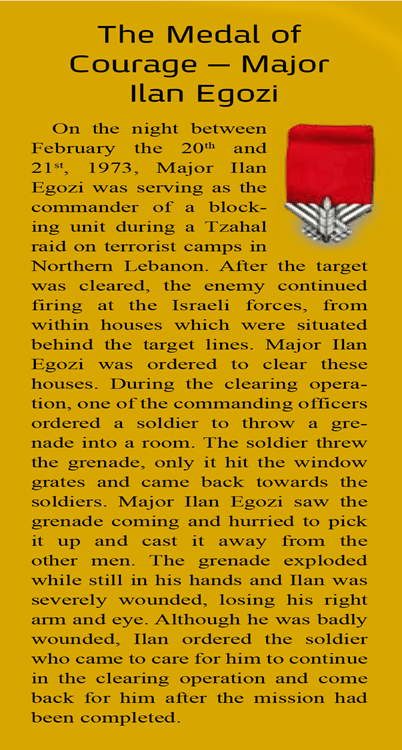

Egozi served in the Navy for 25 years. Most of them spent as a combatant and officer in “Shayetet 13”, the Navy’s Commando Forces. This modest man who vehemently insists he doesn’t have a story, has been through so much during his long tenure as a combatant and career officer: During the Six Day War he was captured and held as a POW in Egypt, took part in dozens of combat missions, the nature of which cannot be disclosed until this very day, he was decorated twice – the Distinguished Services Decoration and the Medal of Courage, one for his bravery and determination during the fierce fighting which took place during the raid on the ‘Isle of Green’ in 1969, and the other for his relentless valor, risking his own life to save that of his men in 1973, near the North Lebanese town of Tripoli, when he jumped to pick up a hand grenade which had rolled towards his men losing his arm and eye as it blew up in his face.

Even after having become a disabled veteran he insisted on returning to serve in his unit and took part in Shayetet missions in Lebanon, operating his rifle with one arm and one prosthetic arm.

Married plus three children, Egozi recently retired from a long, accomplished career as the Executive Director of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Fund. Amongst others, he was responsible for raising funds from Jewish communities the world over. Thanks to funds raised during his tenure and as a result of his vision and sense of mission, together with the very close personal ties he built over the years with donors, the Fund was able to greatly increase the scope of funds raised over the years and to meet the challenges it faced, amongst them building a fourth Beit Halochem center in Beer Sheva, success fully bringing to completion, expansion and renovation projects at existing Beit Halochem facilities and increasing the amount of activities held at the centers, including the Academic Scholarships Project, etc.

Colonel Ilan Egozi being conferred the rank of Colonel by Chief of Staff Lt. General Refael Eitan, and Nili Egozi

He was born on Kibbutz Kfar Menachem, a kibbutz pertaining to the Shomer Ha’Tzair Movement. Egozi remembers a happy childhood amongst his fellow friends. “I spent more time out in the fields than at school, he recounts. “Already as a kid, I fell in love with the outdoors and wide open spaces”.

What brought you to the Naval Commando, why ‘Shayetet 13’?

“I knew nothing about the ‘Shayetet’. Back then it was a very secret unit. Someone on the kibbutz, a year older than I, had been recruited to serve in the ‘Shayetet’ and was kicked off of the unit. He said to me, “Listen Ilan, there’s this unit and when you get to the recruitment base, you should ask to serve in it”.

You must have been very fit. Were you all ‘gung ho’ back then?

Not at all. I was pretty fit, I had good endurance and I was a swimmer. The day I was drafted I asked to enlist in the Shayetet. However, since my qualifications made me eligible for the Air Force’s Flight School, the IDF insisted on sending me to Tel Nof Air Force base to begin the course. At the first orientation talk with the commander of the course he asked, ‘Is there anyone who doesn’t want to be here?’ I got up and said: ‘I don’t want to be here’. The entire course stared at me in amazement and I, in turn, was sent as a punishment to do kitchen duty at Sde Dov Air Force base. After three weeks working in the kitchen I was sent back to the recruitment base where my name already appeared as a candidate for the ‘Shayetet’. Back then it was all very secretive. We weren’t allowed to tell where we are serving, no one spoke about the ‘Shayetet’ nor did they know where its base was located”.

Did you undergo particular tests before you were drafted?

“There were no standard achievement tests as there are today. The main idea was to test just how far a person can drive their body and mind to the edge. There were 80 or 90 of us who were admitted to the training program, most of us kibbutzniks. They took us to Rosh Hanikra, put 20 kg. backpacks on our backs, full gear and a rifle, and said: ‘you will now march from here to Ashqelon, some 180 km. Whoever gets to Ashqelon made it into the course. It was a nightmarish trek. Only 15 of us made it to the end”.

What was the most difficult part of the course?

Col. (res.) Ilan Egozi

“It’s a very long, almost two year course; a combination of physical and mental endurance. There’s a lot of underwater diving at night in freezing cold water. You go into the Haifa Port and dive under boats for three hours. You’re on your own and believe me, there are many good reasons and excuses to want to get out of there and stop the dive, your instructor will have every reason to believe you and has no way of verifying your story. The following day, the cadet has an even greater physical and mental challenge awaiting him and, to overcome it, one has to be very highly motivated as it is only this motivation which will push him forward once the physical strength has drained. Beyond the cardinal physical and mental strain the cadet’s personal credibility plays a key role. You cannot be a fighter in the naval commando if you haven’t got one hundred percent credibility. At the end of the day, you carry out your mission underwater, diving on your own; you need to get to the target and return. No one can really check up on you. You have a thousand reasons why not to complete the mission. If you’re not credible you don’t belong in the unit. This unit works in small squads and each person plays an important role in the group. There were missions in which 4-6 of us took part. It’s enough that one is incompatible and the mission cannot be carried out.

In fact, because of your stubbornness, Israel may have lost a gifted Dakota pilot?

“I want to believe that had I completed Flying School, I would not be flying a Dakota. By the way, my brother completed Flying School so it’s all in the family”.

I’d like to take a leap in time with you to the Six Days War. You were a young officer then. Your squad was sent to dive in the Egyptian Port of Alexandria. There are many different stories about what really happened to you there. I understand things got out of hand.

“In anticipation of the War, we had simulated training on models. The Port of Alexandria was one of those models. The Egyptians had blocked the Strait of Tiran and it was clear to us that war was just a matter of time. The plan was to reach the Port of Alexandria by swimming underwater; we’d take advantage of the surprise factor and be the first to act. Our mission was to sink the main part of the Egyptian fleet, and return back to Israel before it all happens. We left Israel on a submarine two weeks before the outbreak of the War and waited in the open sea. We were cut-off from decks into the water. We affixed the mines. It so happens that these were in fact supply boats and not war vessels. It had already been five hours since we had left the submarine, totally bushed, and far beyond our planned schedule. The navigating equipment that was supposed to guide us was inoperable so a compass is all we had to go by. At dawn’s first light we returned to the meeting place where the submarine was supposed to have been waiting for us but it wasn’t there”.

That is unbelievable.

“We were swimming out in the open sea, in the middle of nowhere and didn’t know what to do”.

Hadn’t you prepared for a possibility that the submarine would not be there? Wasn’t there a Plan “B”? It sounds unreasonable. What were you supposed to do? Swim from Alexandria to Israel?

“The truth of the matter is that it didn’t occur to anyone that the mission would not go through as planned. In any event, under our wet suits we wore our polyester service uniforms and had a gun. According to plan, if anything went wrong, we were supposed to spend 24 hours in hiding near the Port and get back to the meeting point out at sea 24 hours later. At this stage we found ourselves swimming around in circles calling out, perhaps the remaining crew on the sub would hear us. Suddenly, we heard other shouts. It turns out that one of the other couples had also reached the rendezvous point and had not found the submarine. I know that today this all sounds rather absurd but there we were, four combatants in the middle of the sea, facing an enemy port in the middle of a war, shouting at the top of our lungs”.

And no submarine in sight?

“No submarine. Years later, we found out the submarine had engaged in battle with a destroyer which had detected it and even launched a torpedo at it, causing it to have to flee. Only recently, we had an encounter with that submarine’s crew and they explained to us exactly what had transpired that night. In any event, by the time we swam towards it, it was no longer there. This is where the story begins, what do you do? When we realized there’s no submarine, I led the foursome onto a swimmers’ beach south of the Port. On the way we sank our diving gear and as dawn approached we began identifying fishermen boats which had gone out to cast their nets. We reached the shore and I said to the guys:

‘Wait here, I’ll find us a hiding place and return to get you. I began roaming the beach, daylight was all around by now. I came upon a bunch of rocks and between them I discerned a cave. I started shifting the rocks and just like in a Hollywood action movie I discover the third couple hiding. I called the guys and six navy commando men hid in this cave”.

Did you have any food?

“Trust me, when you’re under so much pressure, food is the least of your concerns. In any event, we still had a canteen of water and some condensed food. We could manage until night fall with no problem. Each one was also carrying a gun so we could defend ourselves. It was summer time and the beach was alive with activity. We hid there until evening. Just before darkness fell, one of the young Egyptian boys who had been playing nearby removed one of the rocks to throw it into the sea and discovered us. This was not an easy situation; six Israeli fighters staring at a flabbergasted Egyptian young boy facing us”.

How did you react?

“We debated what we should do with him. Should be catch him? Let him go? In the end we decided to let him go. We said, this is the situation, maybe he didn’t really notice us and if he did, we’re screwed. The beach was near an army base and indeed, within a few minutes we were surrounded by soldiers who led us towards a truck parked close by. I looked around and realized that the Egyptians were stunned by the situation. We walked by a fishing boat marina. I looked around and decided then and there: No matter what happens, I’m running away. I jumped into the water. A friend of mine from my kibbutz, Gadi Patish, jumped in right after me, he did this without having exchanged a word or even a gesture between us. We looked for a place to hide”. “We dived deep under the rocks of the breaker and hid. The Egyptians looked for us like crazy until 3am. Finally, they gave up and left the area. We lay there amongst the rocks, freezing to death, not knowing what to do next. We decided to sneak into the marina, try and take a boat and get out of there. We couldn’t because there were guards everywhere. We were wiped out with exhaustion. It had already been 34 hours since we had left the submarine. We deliberated what should be done and concluded we had nothing to lose. We decided to swim towards Alexandria and walk on the boardwalk. This was an affluent neighborhood where Alexandria’s wealthy community lived. We assumed foreign diplomats lived there, too. We thought we’d seek asylum at one of the Embassies. This is what we did. We began knocking on doors”.

Are you serious?

“Yes. We were wearing our service uniforms, walking in woolen socks and had our dog tags on us, because we didn’t want to be caught as spies, and hoped to find asylum at one of the Embassies”.

What goes through one’s head? You just want this nightmare to end?

“On the one hand you don’t want to get caught, but we were so, so tired, we just wanted it to be over”.

Did anyone open the door for you?

“Not a single one. It was already almost 7am and we decided to walk through the city and see what happens. We hoped to steal a car and get out of town. In our wildest dreams, neither of us imagined we would find ourselves in such a predicament, nor could we, under these circumstances therefore, come up with a plan”.

It’s unreal. You and your childhood friend from the kibbutz are walking barefoot in the streets of Alexandria in the middle of the War.

“Yeah, out of the entire IDF, what are the odds that two of us childhood buddies, from the same kibbutz, find ourselves in this imaginary scenario. Without realizing it we were actually approaching a closed military zone. Suddenly, a passerby observing us rather suspiciously turned to us and asked us something seemingly innocent…in Arabic. Unfortunately, neither of us spoke any Arabic. In a matter of minutes we were surrounded by a mob of dozens ready to lynch us. They confiscated our diving watches, our guns and tried to shoot us in the head. Luckily, after having been immersed underwater for so long, the gun didn’t work.

Fortunately for us all of this took place close to an army base so within seconds soldiers arrived and saved our lives. They brought us to the headquarters and separated us. We were completely drained and wiped out from exhaustion. It had been nearly 40 hours since we had left the submarine, deprived of sleep, food and water”.

You were a POW for nine months. What’s the hardest part of being in captivity?

“Initially, it’s the shock of the transition between being a free person to losing that freedom. At that moment when you feel you are nothing and no one, in other words, you don’t feel human any more, and I’m not talking about the torture”.

Did they torture you to get information out of you or for sadistic satisfaction, too?

“We underwent a lot of torture for the sake of torture. They were merciless. Definitely pure sadism, including use of torture tools and electric shocks to different parts of the body”.

Did they know you were commando combatants?

“I believe they did. There were six of us captured from the same mission and they did cross reference checking. When you’re a POW, you’re completely on your own. I had no idea if or what the others were saying”.

How long were you kept secluded?

“For a very long time I tried to forget and suppress the memories of these months, especially the first stage of my captivity. The period of the interrogations, torture and solitary confinement is a seemingly never-ending stage. That’s why I can’t accurately assess just how long I was on my own. I believe it must have been for at least a month and a half”.

How do you deal with such torture and maintain your sanity?

“I tried to be systematic. I gave them my dog tags and said: ‘This is all I can tell you about me’, and then to myself I said: ‘Do whatever you want to me; I have to keep my mouth shut’. I used to close my eyes, detach myself and float away to distant places”.

Was there any moment when you said to yourself, I wish I would die and get this over with?

“Oh, on many occasions. Many times I’d ask myself how much more of this can I take? There are two main crises in captivity. There’s the stage in which they try to break you physically. That’s when they beat you to death in torture, depriving you of food, spitting on you, tearing you apart. It’s very hard to endure. The main question is will they succeed to break you mentally. That’s your real struggle vis-à-vis your interrogator.

Was there any stage during interrogations when you broke down and started to talk?

“I made up my mind that as long as I could, I’d keep my mouth shut. Indeed, this was the case. ‘Luckily’, during my interrogation and torture I was so badly injured in my throat that even had I wanted to open my mouth I couldn’t. As I a result they had to urgently send me to hospital to treat the wounds they had inflicted on me. For me, it was a week of convalescence”.

Were you afraid they would kill you?

“There’s always that fear, but I knew that being afraid wouldn’t help me. If they want to kill me, nothing will help. They even staged an execution once, but I knew that if they really want to kill me they don’t need this charade”.

What information did they try to get out of you?

“They wanted details about the mission I was caught in, about training, special equipment and names of our commanders. It’s surprising that throughout my captivity they were not aware that I had a brother who was a combat pilot who had actively taken part in the War. If they knew they didn’t relate to it”.

You get into a kind of routine in captivity?

“Yes, after we were all reunited, when the torture had ceased, and after the Red Cross paid us their first visit, we knew that was our insurance policy. There were six of us who had been taken captive; we were joined by two other Navy soldiers who had been taken as well as two pilots. For months ten of us lived in a small room and carried on a kind of daily routine. I think we managed ourselves quite well and in an orderly manner. Obviously, there was the pressure of when will it all end. They continued taking us out for interrogations, and each time they would say tomorrow we are releasing you, but it didn’t happen”.

Were you even aware that the War had ended?

“For a very long time I was not aware of the outcome of the Six Day War. During interrogations they kept saying: ‘We know everything. You shouldn’t hold back because our soldiers have conquered Beer Sheva and we are close to Tel Aviv”.

Did you believe them?

“I had no reason not to. Deep down inside I hoped it wasn’t true, but I was totally cu t off. You’re a POW and you have no idea what’s going on. In Israel everybody was celebrating the huge victory, and I sat in prison with terrible fears that Israel had been conquered”.

Were you sorry you hadn’t captured or killed that youth who had discovered you?

“We saw him drawing close and about to take one of the rocks. Someone said: ‘Guys, he’s coming close; should we grab him or not?’ We deliberated, but hoped that he wouldn’t see us. We hoped that he would take the rock and move away from there without noticing us. When he did see us, it took him a couple of seconds of shock before he ran away”.

How would you sum up your captivity in one sentence?

“A person doesn’t know just how much suffering he can endure until he’s actually there! Never in my life did I believe that I could take so much pain. The mental strength we have is far beyond what we can imagine. This also applies to the disabled veteran’s rehabilitation process. A disabled veteran, who believes in himself, in his mental and emotional strength, has far greater chances to overcome his disability; certainly a lot more than he is aware of. I learned this in captivity. Thanks to that, coping with my injuries was easier in comparison to a young disabled person who has been wounded”.

Was it clear to you you’d be going back to serve in the Shayetet? The Geneva Convention stipulates that if you are captured a second time they have the right to kill you.

“I am not familiar with the Geneva Convention. One thing was clear to me: Having been a POW was a tremendous humiliation and no matter what you did, I felt I couldn’t afford not to return to my unit and continue fighting”.

Were you interrogated upon returning to Israel?

“I returned straight to the Kibbutz, where a party was held in our honor. After two days I was called to come to IDF Headquarters in Tel Aviv, and after another day they told me: ‘Ilan, get on a bus, or hitch a ride, get back to the Shayetet and that’s that”.

I’m moving ahead now to the year 1969, and I’m referring to the raid on the Isle of Green, where you were decorated with the ‘Distinguished Services Medal’. What was the purpose of that mission?

“This was during the War of Attrition; a very difficult period. There were casualties every day. The Egyptians carried out raids in our territory. Our mission was intended to send a clear message to them that they are not immune. The Isle of Green is located at the entrance to the Suez Canal and was highly fortified. It was manned by about 100 Egyptian combatants. They believed it was unconquerable. Israel wanted to show them that we can get to any place in Egypt if we so wish”.

Col. Egozi with his first-born son, Assaf

What went wrong there?

“It was a very complex operation. Twenty of us fighters reached the island swimming; in itself, an extremely difficult operational and logistic feat, which I don’t believe had ever been attempted. We were supposed to climb and conquer it. This is a very difficult raid. The water in the region is totally clear and had they noticed us from above, a couple of hand grenades and we would have been wiped out. It’s frightening. The element of surprise was a key factor in the success of the raid”.

What was your position in the force?

“I commanded the break-in squad. For this purpose, I had reconnoitered the island the previous week to inspect the terrain. The plan was that Shayetet commandos would climb the fortified island and secure its points of entry. Sayeret Matkal (Special Forces) men were to follow in boats, join the break-in force and continue conquering the island. We reached the island and the break-in team under my command, began cutting the fence. I remember we were cutting the wire; I looked up and saw guards walking above me, smoking cigarettes and said to myself: ‘God, it’s impossible not to notice, surely they’ll see us. I knew that the moment they did, not only is that the end of us but it will also be the end of the forces behind us. I saw that we were not able to cut through the fence and thought to myself: ‘enough of these games’. I pin pointed a spot from where one could climb without going through the fence and told the men behind me: ‘this is where we’re climbing-in through and that’s that’. We gave up trying to neutralize the fence, opened fire on the guards and the climb was successful. All went according to plan”. “In fact, the fighting on the island was by squads. Each squad was given a target it had to conquer. The Shayetet force carried out their assignments. Meanwhile, the Sayeret Matkal force that had reached the island on boats, joined the fighting. It was brave fighting by individuals who were groping their way in the dark. We had six casualties and a great number of wounded; some of them from stray bullets. The retreat and evacuation of the force from the island was delayed due to the enormous effort carried out to locate some of those who had been killed. After the main force had left, I remained with a small force; we laid explosive devices and left the island under a barrage of artillery fired at us by the Egyptians from the shore”.

For your actions on the Isle of Green you were decorated with the Distinguished Services Medal.

For your actions on the Isle of Green you were decorated with the Distinguished Services Medal.

“I really think I did what was expected of me and what I had trained for. I didn’t do anything more than that. Not clear to me why I was decorated”.

No doubt it was for nothing…

“No, no, believe me. Everyone who fought on that island, fought in the manner expected of him, not more than I and not less. I mean that”.

Should I quote you why you received it (from the official decoration certificate)?

“I know why. I repeat and I really mean it: each one who took part in that battle, and this is not a cliché, deserves a medal just like mine. I even had the advantage of having done some early recon. I lost some of my closest friends on this mission. I have no doubt that had they been able to tell their stories, each one of them would have been decorated”.

At the end of the day, was the mission successful?

“From a strategic and an operational point of view, it was a very difficult mission and a great number of its goals were achieved. In my opinion, however, the large number of casualties casts a pall on its success. The Egyptians were deeply shocked by the operation. They understood that the games were over. This mission also forced both the Shayetet as well as Sayeret Matkal to seek new methods of operation. Until then, our missions had always been secret, but never of such magnitude. This made us have to think differently. In other words, I’m not saying it all went well or was all bad. It was both. By the way, a very large number of naval commando forces were killed or wounded on this mission and the number of able combatants in the Shayetet after this mission diminished by half”.

Allow me to move on with you to February 1973. Eight months prior to the Yom Kippur War. You’re leading a group of combatants on a raid in the City of Tripoli in Northern Lebanon, back then a ‘Fatah’ stronghold. What was the purpose of the mission?

“This was right after the Haran family murder in Nahariya. The Government of Israel decided that this time we should get into the heart of the terrorist command in Tripoli, taking out as many of its leaders as possible, hitting them in their soft underbelly. This was a large scale raid which included, apart from six naval commando fighters, large paratrooper forces. Our job was to be the first to arrive on shore, neutralize any threat and secure the beach while the paratroopers arrive on boats from the sea. Afterwards, join the paratroopers carrying out the raid as a fighting squad”. “The route leading to our destination was complicated and there was constant fear of being discovered. Despite this we reached our target unnoticed and in absolute surprise. The raid was carried out exactly as planned. I believe about 80% of the terrorists killed were wiped out while asleep in their beds”.

You were critically wounded on this mission and decorated with the Medal of Courage.

“My injury was to a certain degree an idiotic one, but the mission went perfectly well, everything according to plan. I led my squad and we cleared the rooms where the terrorists lived. Throwing a hand grenade and after the explosion the force would go into the room and clear it of its inhabitants. The force moved from house to house. In one of the rooms, the grenade that had been thrown, hit the iron grids on the window and rolled back towards my men. Someone shouted: ‘Grenade!’ And I, in a purely instinctive kind of move, grabbed it with my hand and tried to throw it away from us, but it blew up in my hand”.

Why didn’t you just jump away from it, run away, try to save yourself?

“Listen, a soldier cried ‘Grenade’, the instinct is to kick it or run away. Had I run, people would have gotten hurt because how far can you run? The grenade blows up sideways. At first I thought I’d kick it, but then I was afraid I’d miss it, so in the split second that was left I decided to bend down and try and throw it with my hand. The grenade blew up in my hand when I picked it up and was about to throw it”.

Were you fully conscious the entire time?

“I was completely aware of what was going on”.

According to the IDF Medals and Decorations records it says that the men approached to give you first aid but you sent them off to complete the mission first.

“I told them: ‘Look guys, I’m already wounded, nothing can be done about that. First of all, keep on with the operation’. The fellow who had thrown the hand grenade took it really hard. I said to him: ‘Whatever happened, happened, keep going’. I was really fully conscious”.

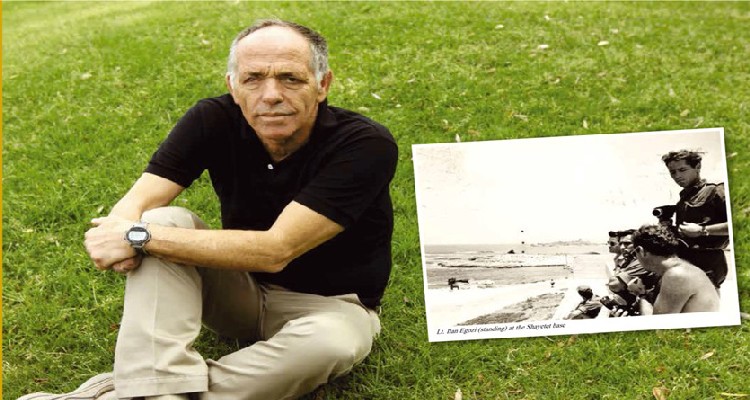

Egozi training at the Shayetet base

In fact you saved the lives of the entire squad.

“With my injury I saved everyone who was close to me. I’m the only one who was wounded. Picking up the grenade was done instinctively, without any thought. On second thought the right thing to do would have been to kick it, but what the heck, that’s a mistake that cost me a Volvo (the car received from the Government A.Z.). One can’t control one’s instincts, they have their own considerations. My instincts were to catch and throw away the grenade”.

I understand a helicopter evacuated you to Rambam Hospital. You had lost an arm, an eye and were badly wounded in the leg. Welcome to the family of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Organization. Did you go through a crisis? From being a fearless fighter, to severely disabled?

“As I mentioned before, I had undergone a far greater crisis. Captivity was a school for life. When they came to cheer me up and comfort me at Rambam, I said, ‘Guys, I really don’t need this. I’m strong enough. I know the reality of my condition and I’ll get over this. I believed I would. I never saw myself as being an invalid. Not for a moment did I ever think there was anything I could not do with one arm”.

You were right-handed before your injury?

“Yes, but you know what, when you have no choice in life, you can do it. In other words, life is stronger than anything else. Within one month I began preparatory courses at the Haifa Technion. I didn’t know how to write with my left hand and I wrote like a moron but that wouldn’t deter me. I looked ahead, thought of what I can do despite the injury. You’ll be surprised, but I believed I could return to the Shayetet”.

You’ve lost an arm, have only one eye and have an injured leg. Isn’t that enough? Why go back to the Shayetet?

“I don’t know. The Yom Kippur War had broken out and it was clear to me I’d be going back to the army, back to the Shayetet. Indeed, during the War, I commanded the Shayetet force in Sharm-el-Sheikh”.

You were reinstated without any problem? Didn’t anyone say, hey, you’re disabled why don’t you stay home?

“I don’t exactly remember how it went. Technically, I was still enrolled at the Technion as a soldier. I hadn’t officially been discharged from the army. A very difficult war had broken out. I went to the Commander of the Shayetet and said: ‘Listen, I have experience, I have know-how, and I’ve got everything’. Before my injury, I commanded the Shayetet training school. My students were training in Sharm-el-Sheikh I knew the sector well. I commanded the Shayetet forces in Sharm. I didn’t fight, I didn’t shoot, and my job was mainly one of command so my injury didn’t really come in the way”.

Legend has it that after the War you returned to the Shayetet and even led men with one arm and one eye, beyond enemy lines”.

“After the War, I completed my degree at the Technion. I was then asked to return to the Shayetet and continue commanding its training school. I returned to that position and it was during this period that I took part in the Shayetet operations in Lebanon, especially landing activities”.

You learned how to operate a rifle with one arm?

“Yes, with a prosthesis. I was in Lebanon, I could definitely have shot, I was very active. We went in swimming, and I did it far better than many of the younger guys. I had experience, I had self-confidence and I was in good shape. Obviously, I was in a command position and not in the first line, but my knowledge and confidence, acquired over time, helped me a lot in this position”.

Didn’t your wife say, ‘Ilan, enough!’

“My wife and I met while both serving in the Shayetet. She knew me well. She knew there are things she couldn’t say to me”.

You were discharged from the IDF as a Colonel.

“I continued serving in the army. I understood that despite the privilege and because of my physical limitations, I wouldn’t be able to serve as Commander of the Shayetet. I understood that the moment I was wounded put an end to my chances. I agreed to return to the Shayetet to command the training school. After that I moved on to the Navy Headquarters as a Colonel. At the same time I also enrolled at Tel Aviv University to do my Masters in Business Administration. I was discharged in 1987.

Were you familiar with the Zahal Disabled Veterans Organization before you were appointed Executive Director of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Fund?

“When I served at Navy Headquarters I used to come to Beit Halochem to work out. Back then Beit Halochem was surrounded by sand and I’d run in the sand. I was familiar with the sand and with the showers. I didn’t know the ZDVO. Let’s say I was acquainted with Beit Halochem and its activities, but not with the organization. After I completed my job with the Jewish National Fund (Keren Kayemet Leyisrael), I was asked by them to be a Shaliach on their behalf in the UK for two years.

It morphed into five. It was the former ZDVO Chairman Yoske Lutenberg who knew me from the years I served in the Shayetet and who brought me to serve in the Zahal Disabled Veterans Fund.

Most Zahal Disabled Veterans are not familiar with the Zahal Disabled Veterans Fund. They aren’t aware that it is in fact the heart of the ZDVO. In a few words, what is the role of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Fund (ZDVF)?

“The ZDVF is only the fund raising branch of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Organization. The true human resource and the heart of the ZDVO are the disabled veterans. That’s a big difference”.

I stand corrected.

“Anyone who works at the ZDVO works for the benefit of the disabled veterans. But it is the same disabled veterans who must understand that to succeed in this important mission requires their cooperation, too. It requires them to be involved in this work instead of just sitting down and saying: ‘serve us’. Without cooperation, we won’t get anywhere. A disabled veteran must know that if he doesn’t give 100% of himself, he will not rehabilitate. I pushed myself through my rehabilitation, constantly setting challenges to meet. Even after my most severe injury I never saw myself as being disabled. This is a very important factor in one’s rehabilitation.

From your managerial experience at the ZDVO, what is the main role of the Zahal Disabled Veterans Organization?

“The ZDVO’s main role is to build an efficient organ that places the rehabilitation of its members at the top of its priorities. It should be kept ‘clean’ and innovative, an organization whose members will be happy to be a part of and the State of Israel will be proud of, too. I hope all this doesn’t sound too much like a cliché”.

Can you be more specific?

“I don’t think there’s any need to explain. It’s important for me to emphasize that the ZDVO owes a great debt of gratitude to the many donors, especially to the Chairmen of the ‘Friends’ organizations abroad who work tirelessly to raise funds and view this work as a mission. They also invest their time and energy in strengthening the ties with the members of the organization”.

As a former POW, should the State of Israel pay any and all price for the release of one of our soldiers being held in captivity?

“Listen, this is my personal opinion and it doesn’t count for anything. When I went to war and was captured by enemy forces I thought the State of Israel should do everything possible to bring back its soldiers. Everything but not at all cost. I believed that even a price has a price. When I was in captivity, I hoped I’d come back. One’s ability to survive depends a great deal on holding on to the hope of returning home. However, I knew that war comes at a cost and that I may have to remain imprisoned a long while. I was ready for it. You know, we could have been released much sooner, but we all made a conscious decision to stay in captivity as long as it took to secure a package deal for the members of the “Mishap” to be released together with us (also known as the ‘Lavon Affair’; this was the group of Egyptian Jews apprehended in the 1950s by the Egyptians and accused of espionage for Israel) who had been rotting in Egyptian jails for the past 14 years”.

Ilan, I have known you for many years and I don’t know many Israelis who can be credited with so much accomplishment, decoration and merit, and I say this with all my heart.

“I won’t let you print that in the interview”

I also know that you are a very modest person. If I hadn’t held you ‘with your back against the wall’ this interview would not have been born. When you think back on the days you volunteered to serve in the Naval Commando and when you look at Israel in 2013, are you satisfied, are you disappointed?

“When I was 18-20 yrs. old I looked at life differently. I was an idealist. I was raised idealistically on the kibbutz. I wasn’t even familiar with the concept of ‘materialism’. We can’t deny that our world today is a different one. It has its advantages and disadvantages. I very much miss those values of back then. At the same time, today’s world is so much more advanced and developed. If one could combine the two we’d be living in a better place”.

Finally, if you were 18 yrs. old again, after everything you’ve been through and with the insight you have today, would you join the Shayetet again?

“Obviously, I have been cut off from the Shayetet for many years. About a month ago their commander invited me to give a talk to the fighters who are about to join officers’ cadet course. They are the salt of the earth. Amazing young men, each and every one of them, deeply instilled with values. I would be proud to serve in the Shayetet at their side”

Comments are closed.